Ideas Written in Stone - The Jewish Chronicle

Architecture is the embodiment of the central concepts of each religion, ideas written in stone as the Gothic Cathedrals have often been called. So important are the temples, chapels and sites of religion, that one source of the Mideast conflict are the conflicting claims to Jerusalem; specifically the Temple Mount by Israel, representing Judaism, and Islam, by the Arabic countries of the region.

In the Middle Ages, Christian nations fought the Crusades to wrest control of Jerusalem, site of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus; from Islamic kingdoms who had already built the Dome of the Rock mosque atop the site of the Holy Temple of Solomon.

The sober holiday of Tish B’Av characterized by prayers and fasting, commemorates the destruction of both temples in Jerusalem, by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and the Romans in 70 AD. Traditionally attributed to God’s will for the sins of Israel, the destruction of the Temple marked the dispersion of the Jewish people from the centre of their faith.

When architecture is linked to religion, passions are aroused that are not easily assuaged.

For the Temple it was not simply the pilgrimage point of the Jewish religion, but the Torah considered it to be the centre of the world itself, and the rock upon which it was built to be the origin stone of the universe. In the Zohar VI:

“The land of Israel sits in the centre of the world, Jerusalem in the centre of the land of Israel, the Temple in the centre of Jerusalem, the sanctuary in the centre of the Temple, the ark in the centre of the sanctuary, and in front of the Ark, the Foundation Stone, from which the world was founded. This is the Foundation stone, centric point of the entire universe, upon which stands the Holy of Holies.”

This belief is not limited to Judaism but is common to many faiths, from Hindu temples to sacred shrines around the world.

There are two spatial dimensions to the idea of sacred space that are essential to the nature of architecture, the horizontal and the vertical.

The horizontal is characterized in exodus by God’s warning to Moses not to approach the burning bush, “Do not come near to here, put off your sandal from your foot, for the place upon which you stand is holy ground.”

The theme is reiterated at a larger scale in the Revelation at Sinai “The people are not able to go up Mt. Sinai, for you yourself warned us, fix boundaries for the mountain and make it holy”.

Concentric rings of increasingly holiness characterize sacred space. The separation of the holy from the everyday or the profane is a theme repeated in the great upright boulders of Stonehenge, creating the inner ring of the mysterious site, to the maze on the floor of Chartres Cathedral, aptly named Chemin de Jerusalem the “Road to Jerusalem”.

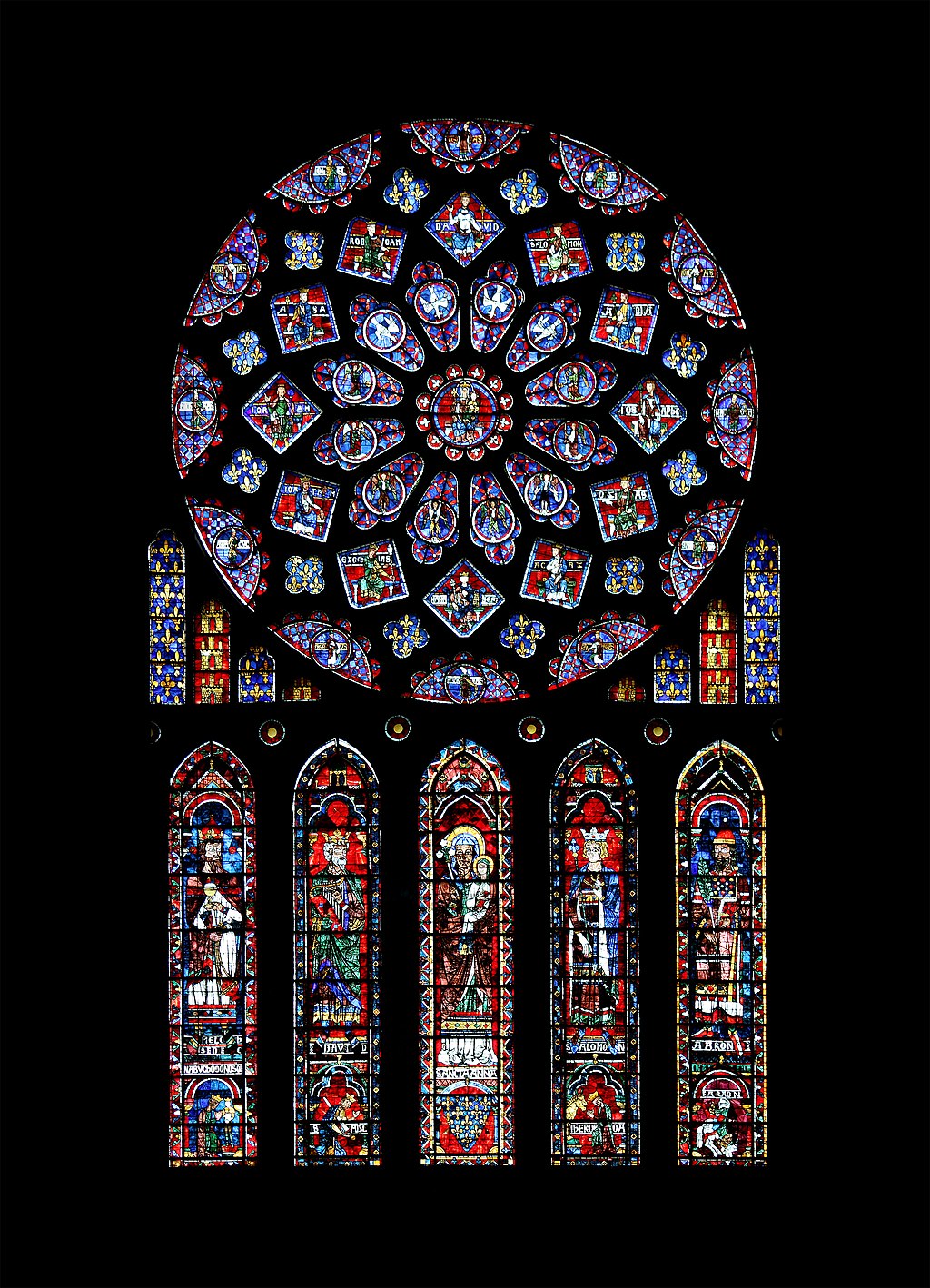

Chartres was the earthly incarnation of the New Jerusalem described in the book of Revelation by Saint John the Divine: “And the twelve gates were twelve pearls… and the street of the city was pure gold, as it were transparent glass.”

This is an extraordinary extrapolation of the various descriptions of the Temple in Jerusalem, in the book of Kings’ Chronicles and the most extensive in the Book of Ezekiel, where he is led around by an angel “with a line of flax in his hand, and a measuring reed” and is shown in great detail all the gates, courts and inner sanctum of the Temple complex. The holy temple is a series of concentric courts of increasing sanctity culminating in the Holy of Holies, described as a cube of space without windows, in which there was nothing but the ark holding the tablets of the Ten Commandments.

In Revelation, the entire city is a cube of luminous glass. The jeweled light of the holy foundation stones of the New Jerusalem, based upon the stones on the breastplate of the Levites are now the celestial colors of the magnificent stained glass of the Gothic Cathedral. In the Zohar, the Kabbalistic Book of Radiance, the idea of the Jewish Holy of Holies in darkness is revised into an ambiguity of simultaneous dark and light: “A spark of impenetrable darkness flashed within the concealed of the concealed from the head of Infinity — a cluster of vapour forming in formlessness, thrust in a ring, not white, not black, not red, not green, no color at all. As a cord surveyed, it yielded radiant colors.” (Zohar: Parashat Be-Reshit)

The second idea of sacred space concerns verticality, the axis mundi linking heaven and earth, as exemplified by the upright stone pillar of Beth-el, where Jacob has his dream of a ladder reaching to heaven, with angels ascending and descending.

The axis mundi organizes the cosmic mountain that connects the earth to the Divine realm. The great Buddhist stupa of Borobudur in central Java, built from the 8th -10th century, is the example par excellence, a mandala in three dimensions, the plan is a cosmic diagram of the universe according to Buddhist concepts.

A series of square and circular terraces, each conforms to a different principle of Buddhism, from the lower levels that correspond to the sphere of desires; the second to the sphere of formlessness where we abandon desire but are still linked to name and form.

Finally, the upper terrace is the sphere of formlessness, where the Buddha has reached Nirvana and is released from the body.

The uppermost terrace is circular and is populated by pavilions with statues of Buddhas, some of which are partially uncovered.

The space matches exactly the sublime and magnificent concept of ascent to the heavenly realm; the terraces are completely open to the dome of the sky and the distant horizon.

The Pyramids of Egypt are vertical axes linking heaven and earth in a monumental, yet completely abstract manner.

The triangular form captures the solidified outline of the rays of the sun, the arms of the god Ra, radiating out from the intense yellow disc and pointing up to the center of the dome of heaven, the axis upon which the sphere of the world itself rotates. Just as the Temple on earth is a copy of the heavenly model as told in the Zohar, “by this mystery, the dwelling was formed and constructed, being in the image of the world above and in the image of the world below.”

Each human is a microcosm of the Temple and in turn the universe itself.

This is clearly shown in the Hindu Kundalini yoga diagram, where the central axis of the spine is a miniature axis mundi linking the individual human to the hierarchy of earth and sky. It is a ladder to be ascended, from the lower chakras or energy points of animal-like desire to the transcendent higher chakras of revelation and nirvana where the spirit is released from the body.

Remarkably, the Kundalini is similar to the Kabbalistic diagram of the Sefirot, the emanations of the attributes of God from a source in the infinite in to the visible world below. It is also shown metaphorically in the shape of Adam Kadmon, the primordial first man at the time of the Creation.When the ten points of the Sefirot are mapped onto a man, a similar hierarchy is also perceived, from the lower points of the phallus (Yesod) to the crown (Keter), symbolizing of course the range of levels of consciousness in an individual.

This is perceived metaphorically in a religious structure in the procession from the public and profane world of the exterior to the increasingly more holy interior space, culminating in the ark of the synagogue or the high altar of a church.