Governor's Palace of Chandigarh - Oppositions

An Analysis of the Governor's Palace of Chandigarh

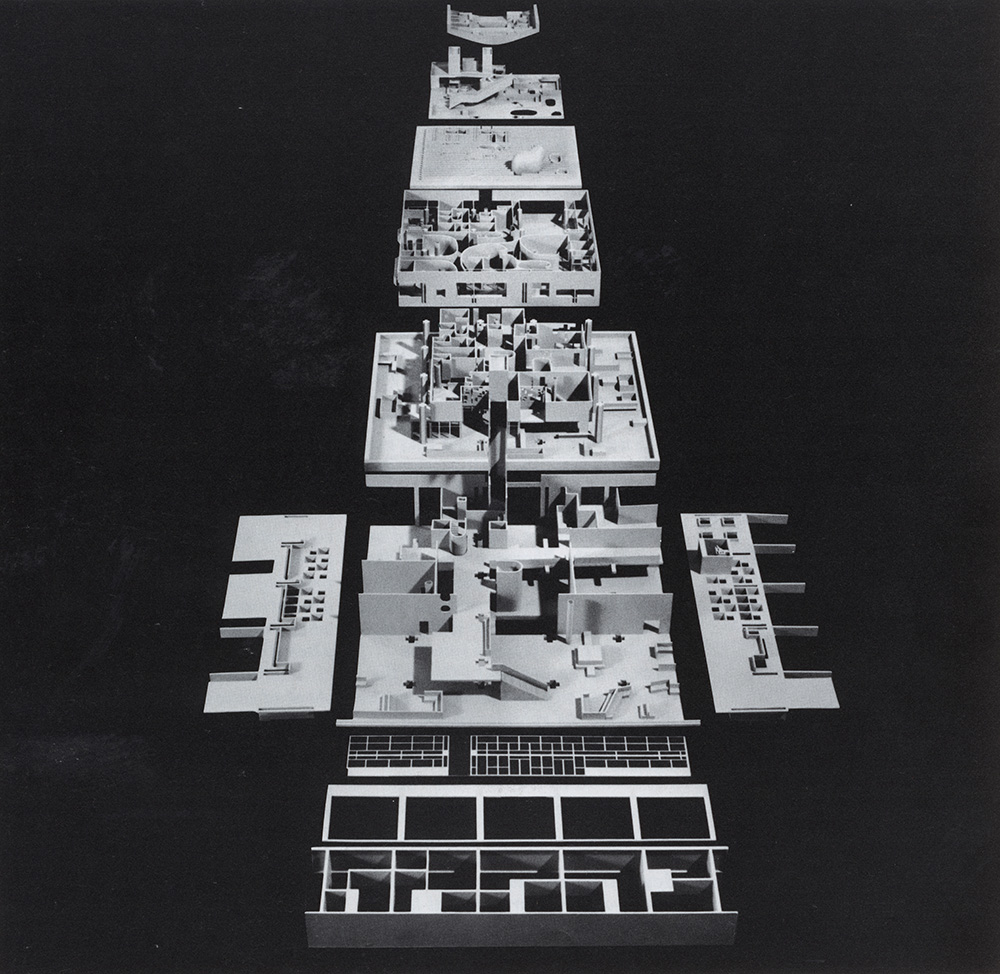

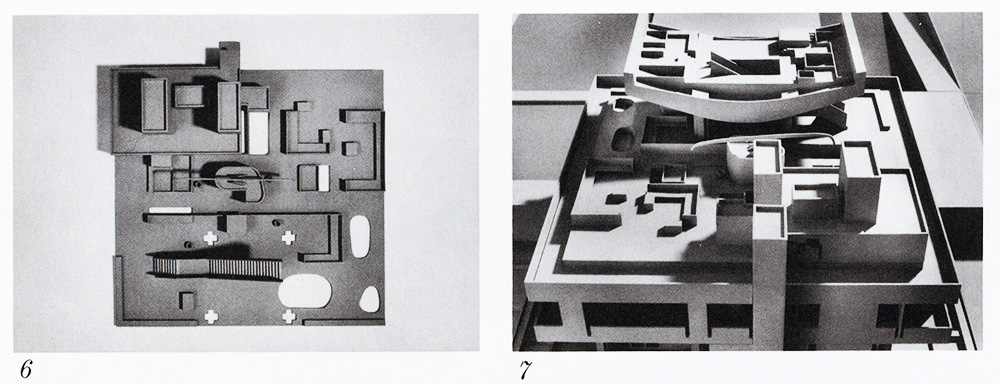

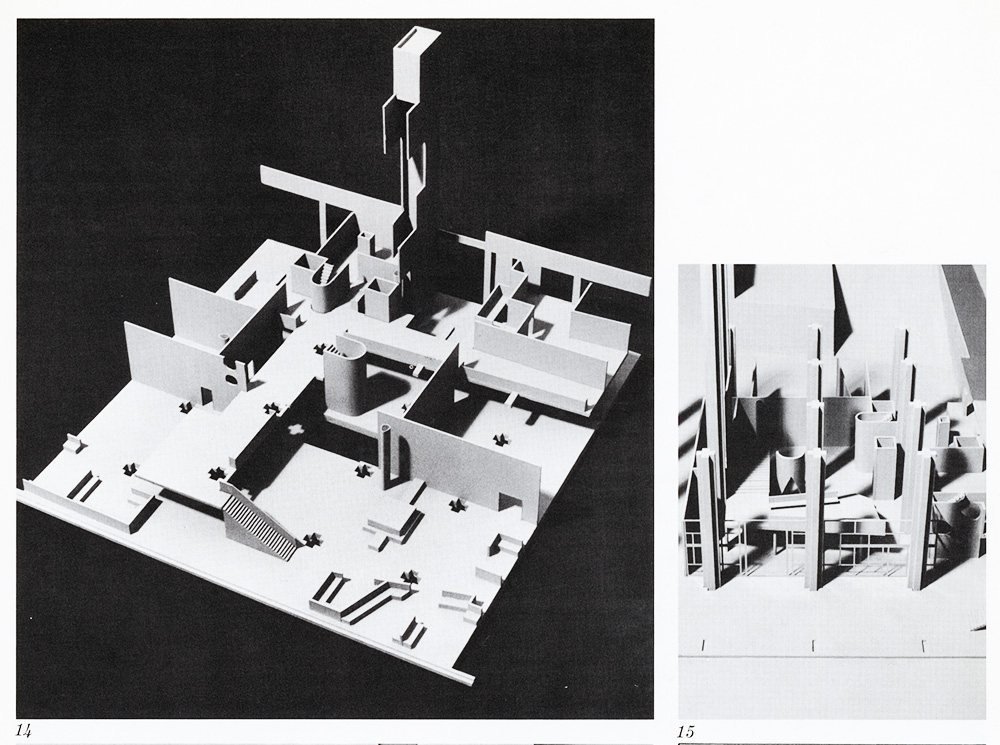

The pyramidal mass of the Governor's Palace was to be placed directly against the silhouette of the Himalayas (figs. 1-16), at the apex of the capital city of Chandigarh. By presenting the palace as the "crown of the capital," Le Corbusier emphasized its function as the city's symbolic focus. Its position at the edge of Chandigarh was intended, like the Egyptian pyramids, to define the boundary between civilization and nature. Yet despite its importance, it was the single government building of the capital complex of Legislative Assembly, High Court, and Secretariat that was not built.

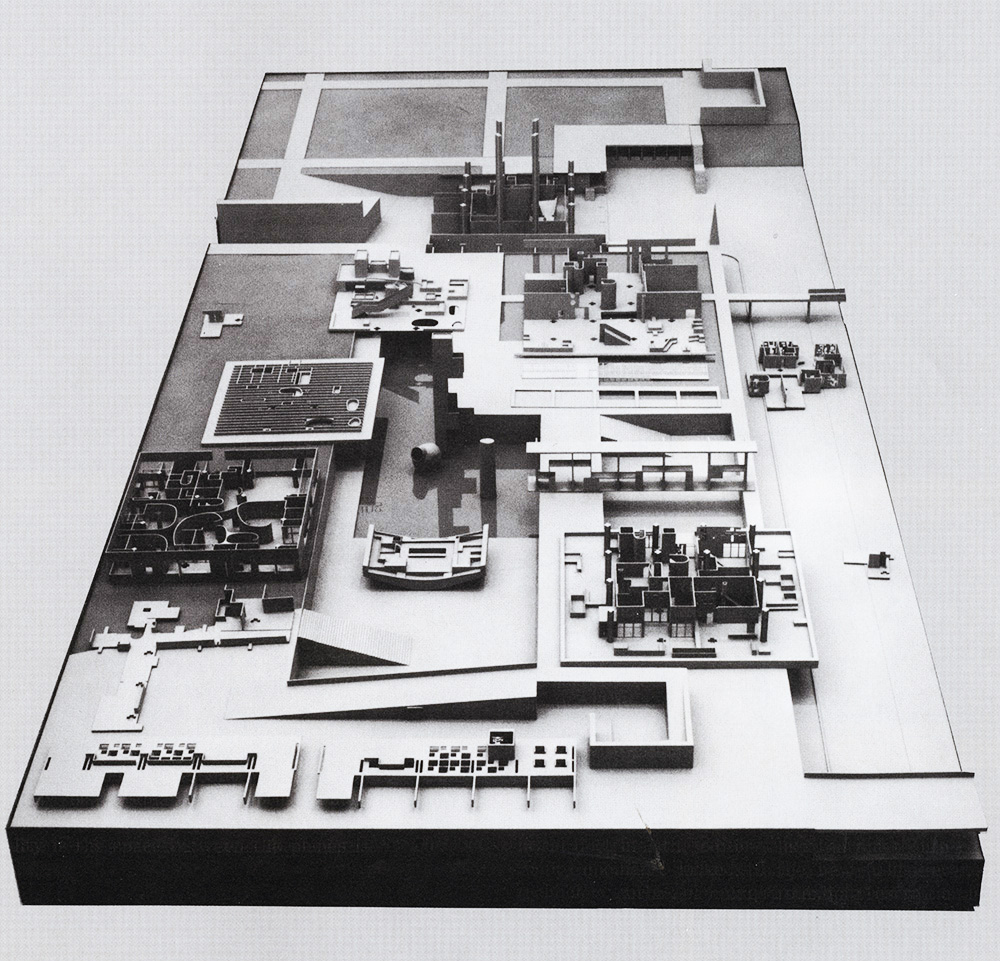

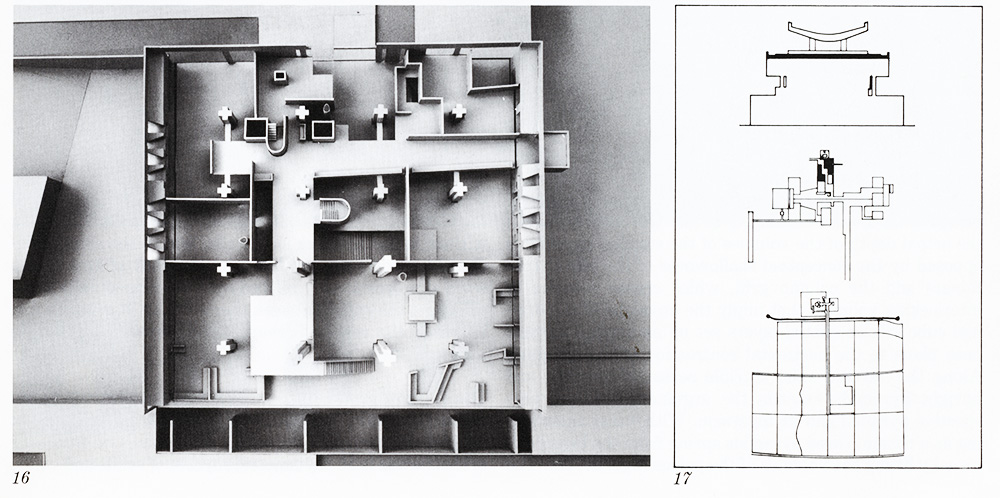

In his attempt to bring modern architecture to India, Le Corbusier synthesized certain native mythical themes with machine age myths of the early twentieth century, fulfilling in Chandigarh his statement that "new cities are also in part ancient cities." Proposing the metaphor of the city as a biological organism in the image of man, as in The Radiant City of 1935, Le Corbusier appears in a photograph holding a plan of Chandigarh beside the Modulor figure. Reiterating the theme, the Governor's Palace is appropriately presented next to its turbaned Indian model maker. The theme of the city as body, the capitol as head, and the palace as crown is further articulated in the actual plan by three pairs of axes, with water mediating between each set (fig. 17). A canal divides the axis linking the city and capitol, pools separate the capitol from the palace, and within the building itself an elevated water trough to catch the monsoon rains detaches the rectilinear base from the hovering curve of the viewing platform (barsati). As expressed in the original sketches of Chandigarh, the play between right angle and tensed curve is most clearly realized in the silhouette of the Governor's Palace. A similar relationship appears in the section of the High Court, the portico of the Legislative Assembly, and the form of the Monument of the Open Hand.

Connected by footbridge to the palace is the plaza and sculpture of the Open Hand. It is a personal symbol equally of Le Corbusier and of Buddha, whose open hand indicates blessing. Its path of approach virtually mirrors that of the Governor's Palace, although in conception they are reversed (see fig. 4); the path to the palace is conceptually solid while the path to the Open Hand is a recessed void. The visual work, previously analyzed by Le Corbusier as "measurable elements in harmony or opposition," is in Chandigarh characterized by a complementary play of formal oppositions. Through this means, the stepped pyramid, which the Governor's Palace resembles at one level, is reinterpreted in a way which takes such traditional formal references and places them in tension with their modern counterparts.

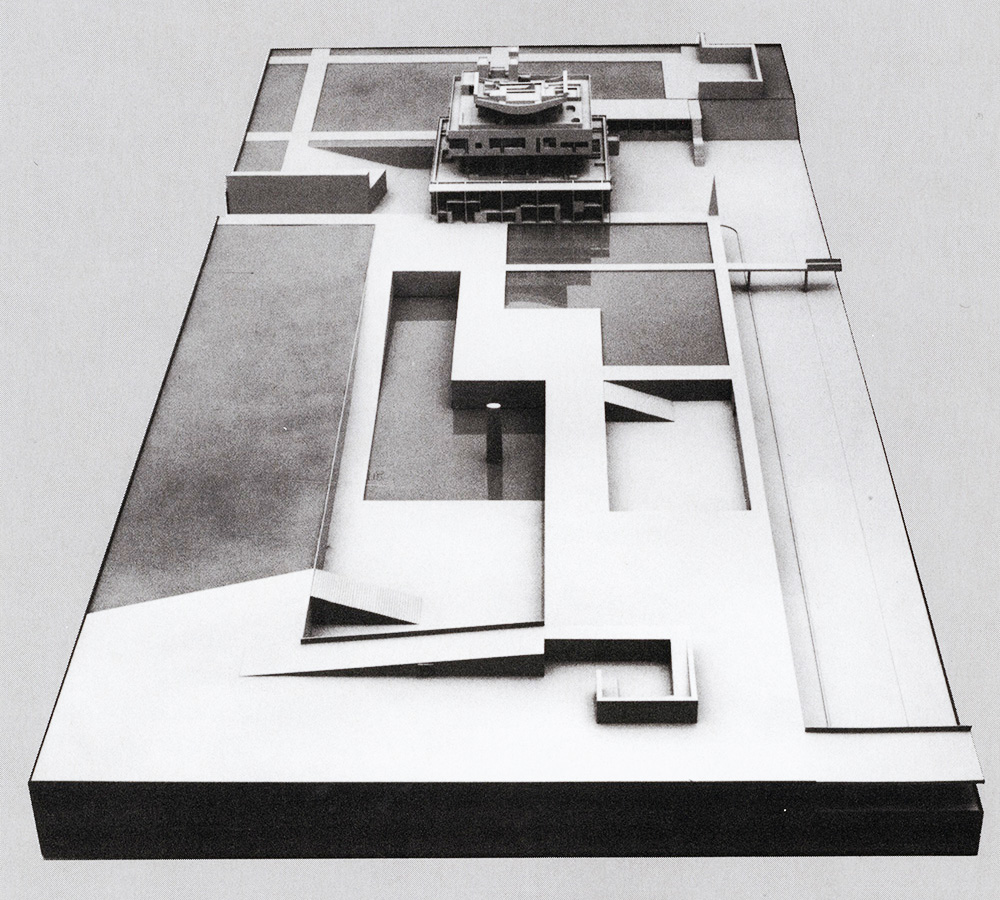

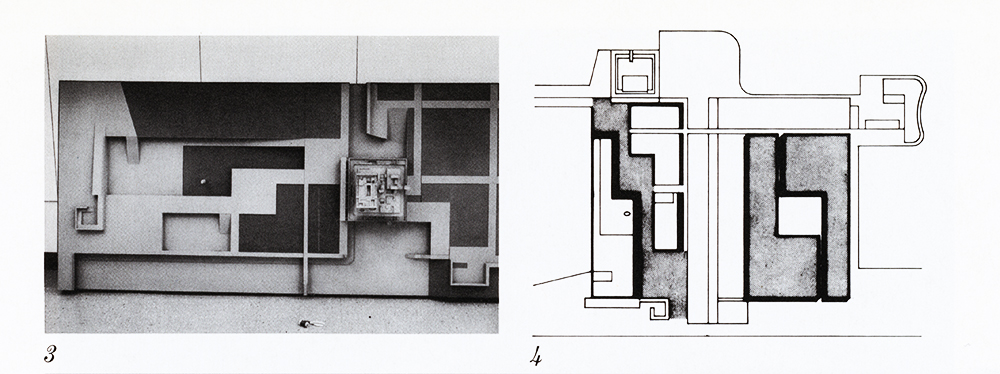

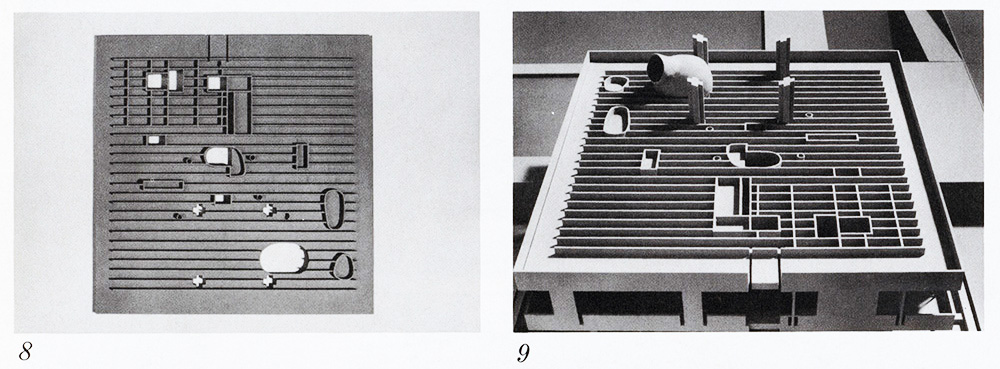

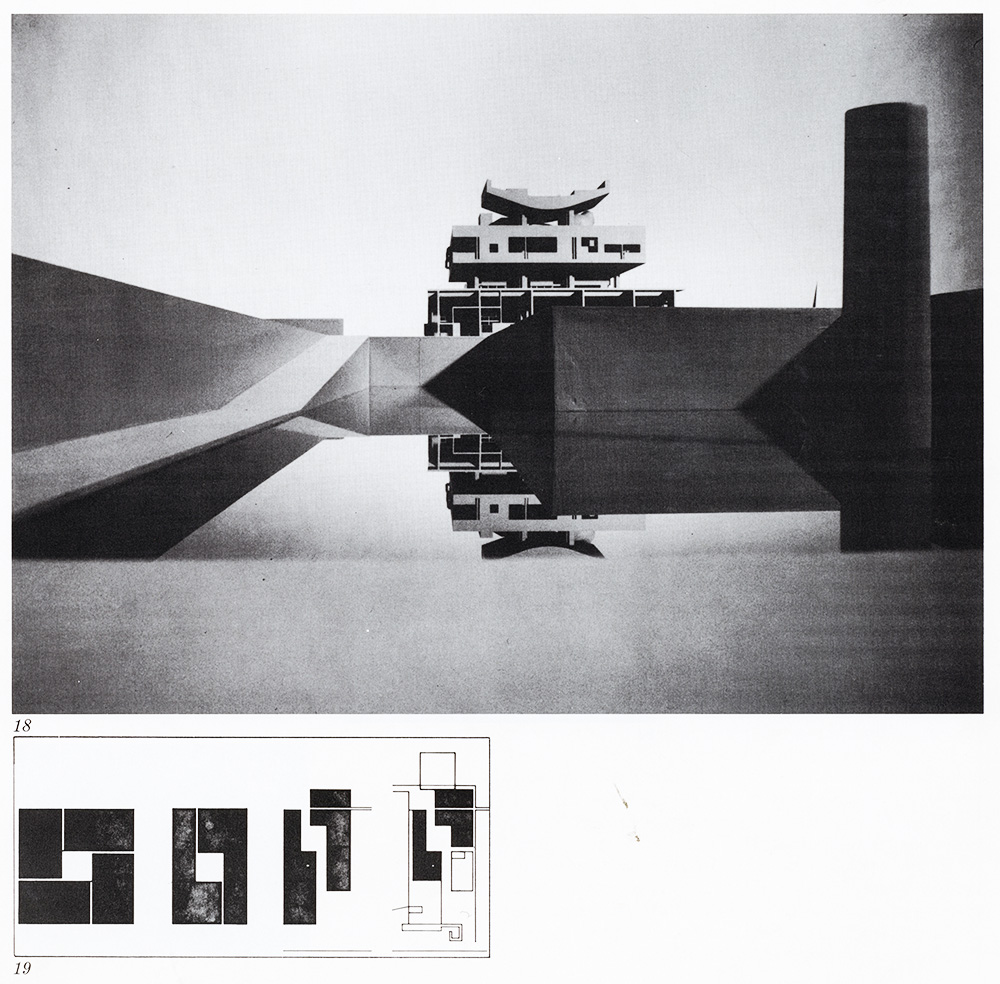

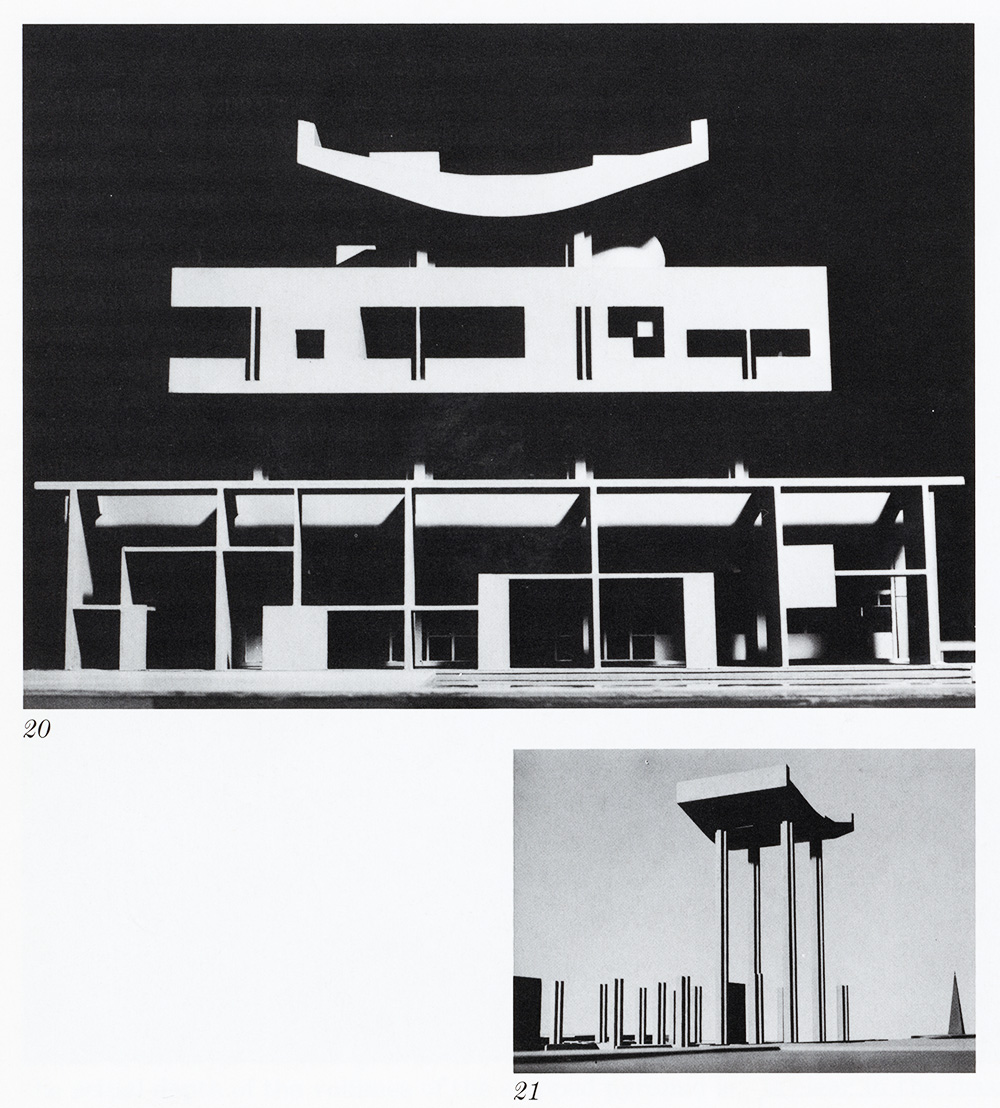

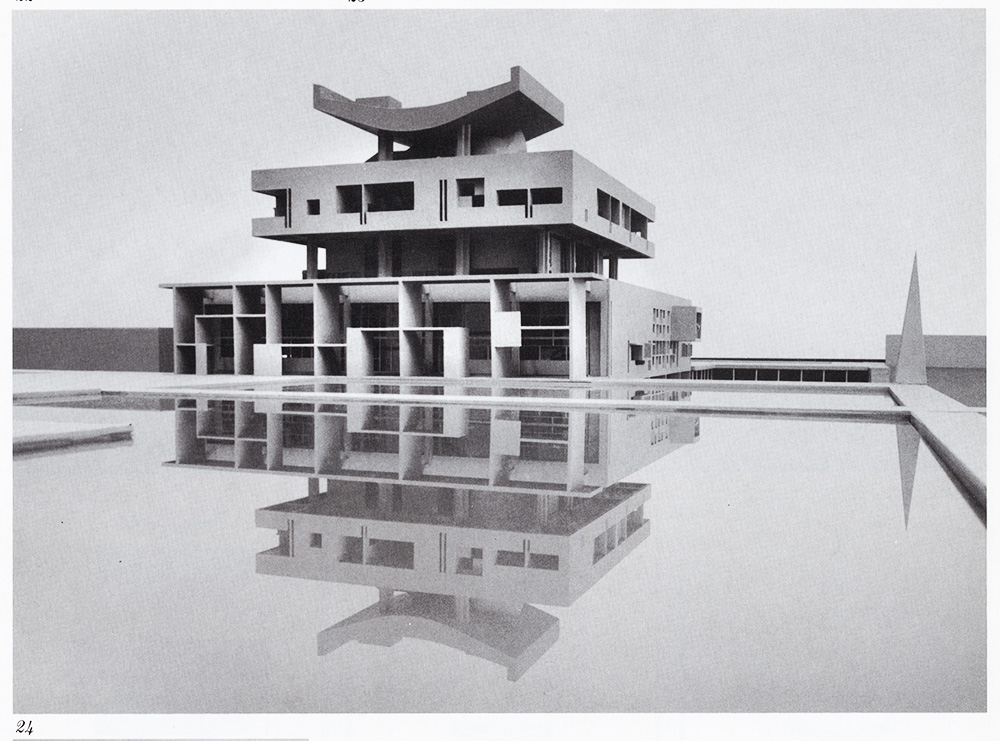

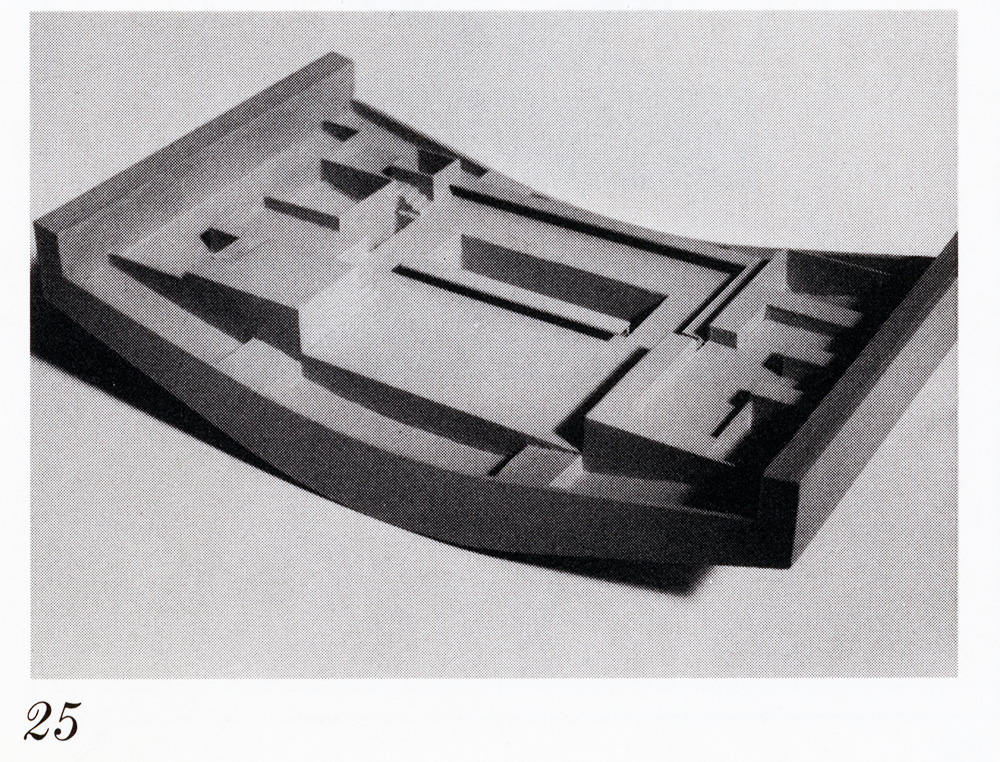

The palace is situated at the end of an enclosed precinct of multi-level gardens and pools (see fig. 2). This seemingly ancient forecourt of giant ramps, stairs, and obelisks rising from the water belies its modern articulation. The original sketches show a static, symmetrical approach to the palace, while in the final design the axis is broken, creating a shifting series of plazas before the palace. The garden is framed in plan by two interlocking L's, a form derived from the rotation of the arms of a spiral. The pedestrian ascends the Martyr's Ramp to find the distant palace visually thrust forward. The garden levels fall away in shearing blocks as the reflecting pools double their height, creating a foreground and plinth for the palace, which enforces the image of a temple on an acropolis (fig. 18). Descending the spiral ramp, a counter-spiral activates the procession to the palace. The collapsed arms of the spiral compress its centripetal force into a dynamic push-pull effected by the pressing forward of the pools against their static frames (fig. 19). As the three plazas shift to the left, the palace oscillates between two obelisks, a cylinder, and a pyramid, shifting the eye to the mountains and the Open Hand monument to the right. Finally, the dense symmetrical mass of the palace wrenches the eye to the center, to settle in the curve of the barsati, an elevated valley framing the Himalayas (figs. 20, 21, 25).

The purpose of this forecourt was to visually link the palace with the plaza between the Assembly and High Court. Le Corbusier feared that "by optical illusion, this distance would be disastrously increased," so that the palace would be lost in the background. In this "linking of distant objects," the deep space of the traditional processional axis is visually compressed through perspective distortion. Looking toward the palace, the reflected incline of the ramp forms a horizontal pyramid, its position facing the viewer neutralizing the perception of distance (see fig. 18). At the far end, the pyramidal obelisk terminates the converging path, affecting the illusion of a vertical tilt of the perspective. Completing the triad are the reflections of the obelisk and the palace, each forming a diamond suspended between water and sky (fig. 24).

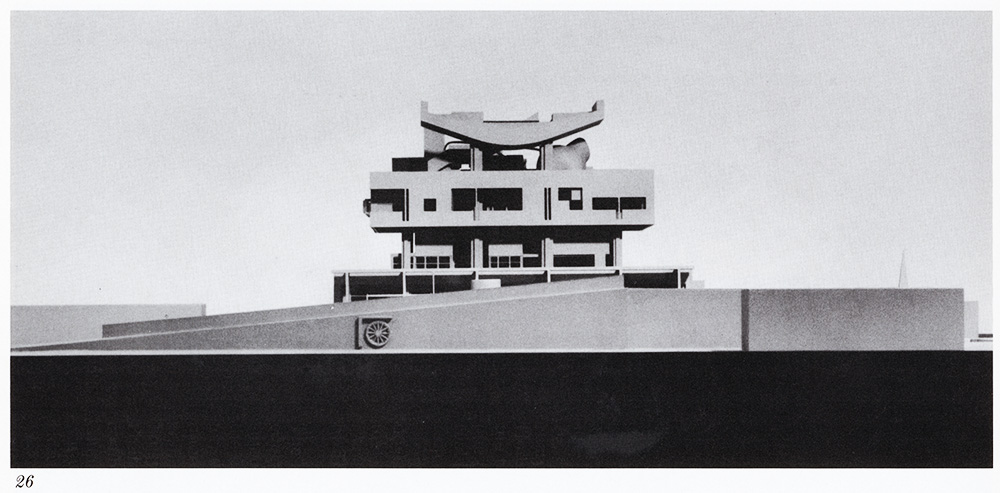

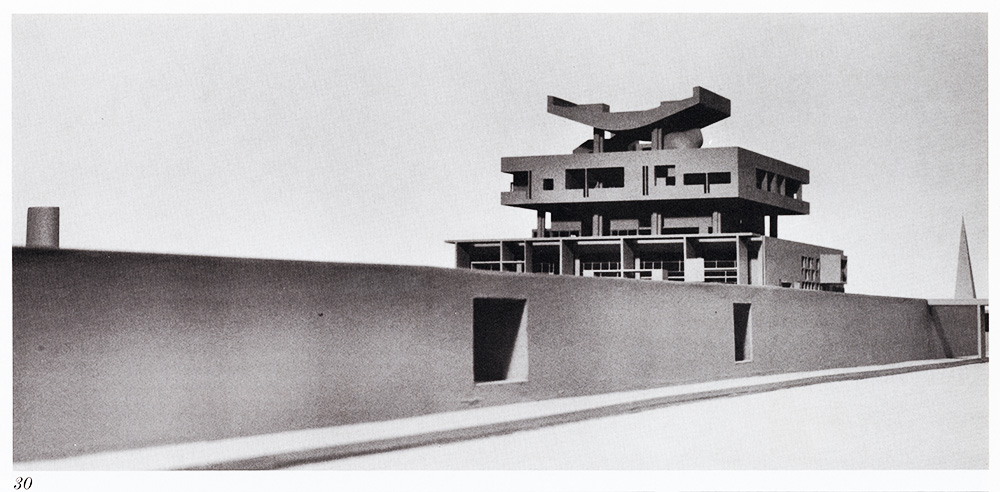

Inside the garden, the counter-illusion to increased distance is developed as the sidewall, ramp, and stair reflect and slant into a perspective pyramid of great depth. The contrast between actual and implied depth is clear in the separate views allowed to the pedestrian and the automobile. From the road, one sees the palace atop the flank of the garden wall, diagonally foreshortened in perspective. Reproducing this relationship, though only implying depth, is the frontalized diagonal of the Martyr's Ramp (figs. 26, 30). The entire site summarizes these perceptual vibrations in the yin-yang formation of the two interlocking L's; the convergence of the one, increasing the illusion of distance, is countered by the divergence of the other.

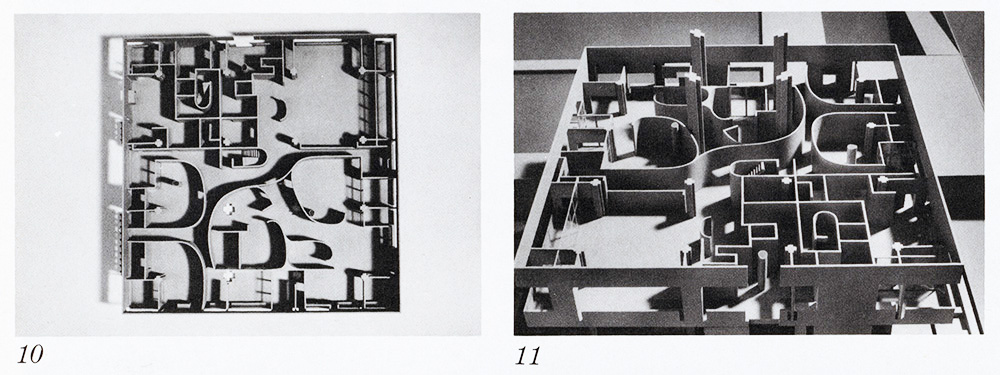

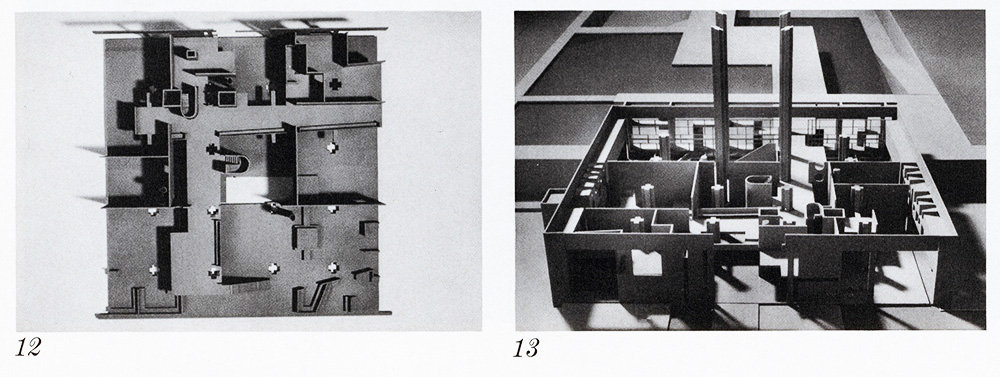

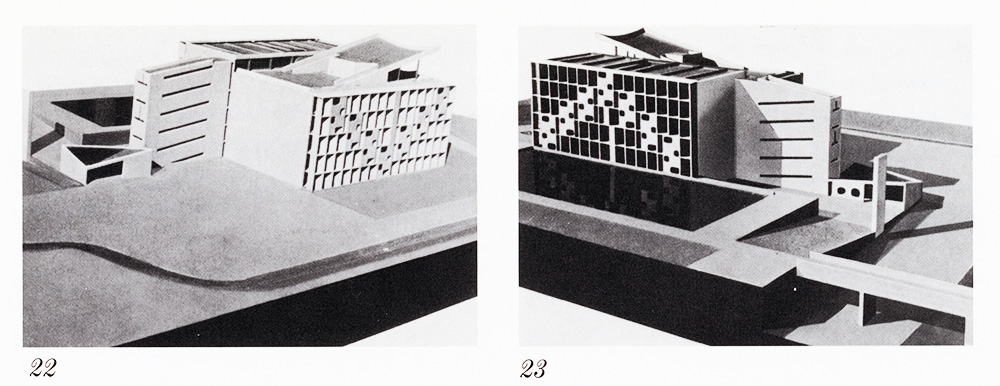

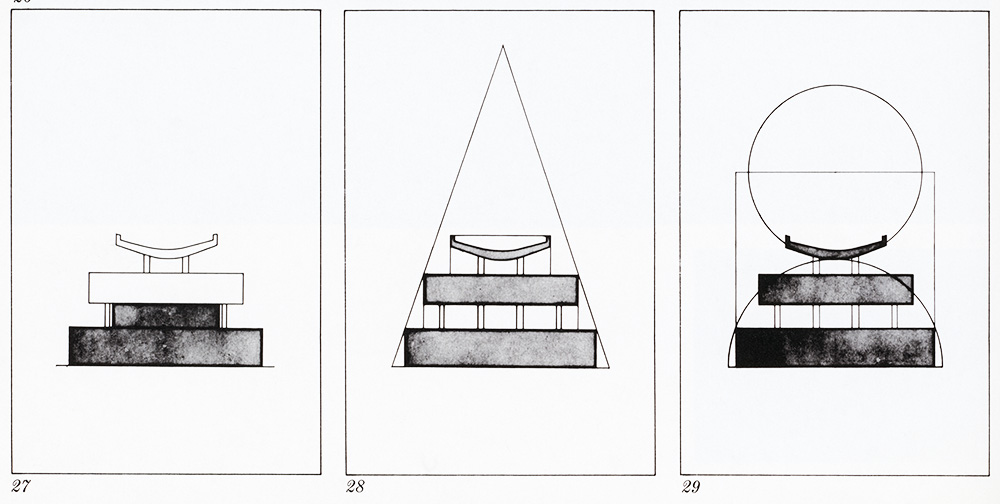

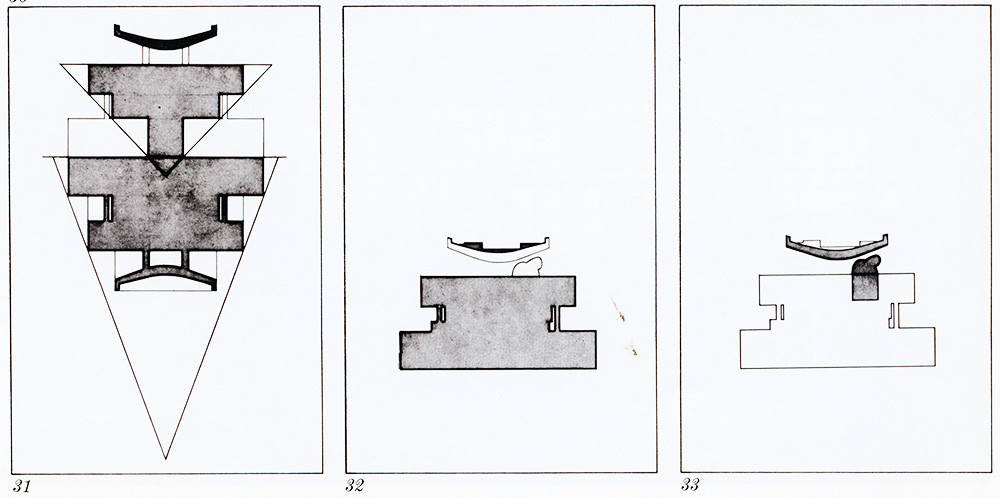

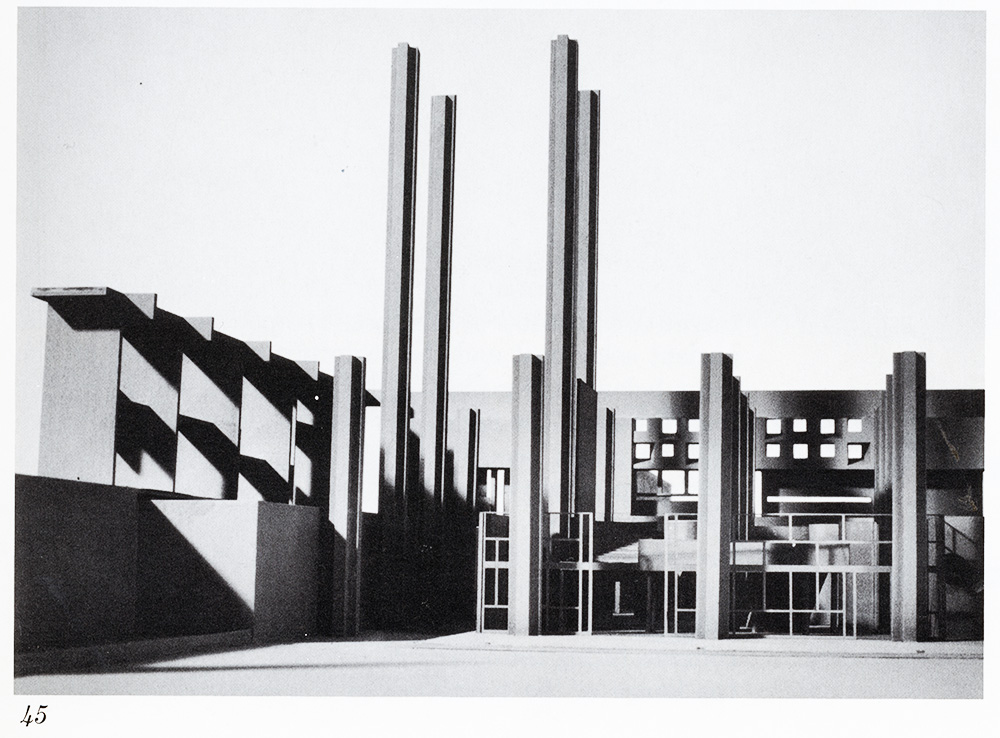

This dialogue between traditional deep space and modern-ist shallow space, signified by the perspective pyramid of Renaissance and its Cubist inversion, is evident on the facade of the Museum of Knowledge,5 designed to occupy the site of the Governor's Palace after the palace was rejected (figs. 22, 23). Here the actual frontal plane the cube is countered by the arrangement of the stair screens into a triangle of implied depth, while on the rear facade is an inverted triangle. In the Governor's Palace, the actual depth of the volumes of the stepped pyramid is by the conceptual shallowness of the planar containers and the column grid, which create a series of volumes that imply the envelope of the original cube. These spatial layers set up an implied vertical base plane to the horizontal contraction of the pyramid. Along the vertical axis, a triple series of inverted and upright pyramids extends the argument between perspective pyramid and its inversion. With water again acting as a datum, three pyramids spring from the base pool, visually lifting the volumes of the palace (figs. 27, 28). The vertical movement is halted and reversed by the centrally tensed, inverted curve of the barsati, creating a tremendous concave-convex pressure, barely contained within the implied pyramid boundary (fig. 29). Its inverted form is echoed in the pyramid hung from the elevated water trough and in the reflected image of the palace (fig. 31). The solid, right-angled base is inverted in outline within the curved void above, itself reversed in the solid curve of the prayer room below (figs. 32, 33).

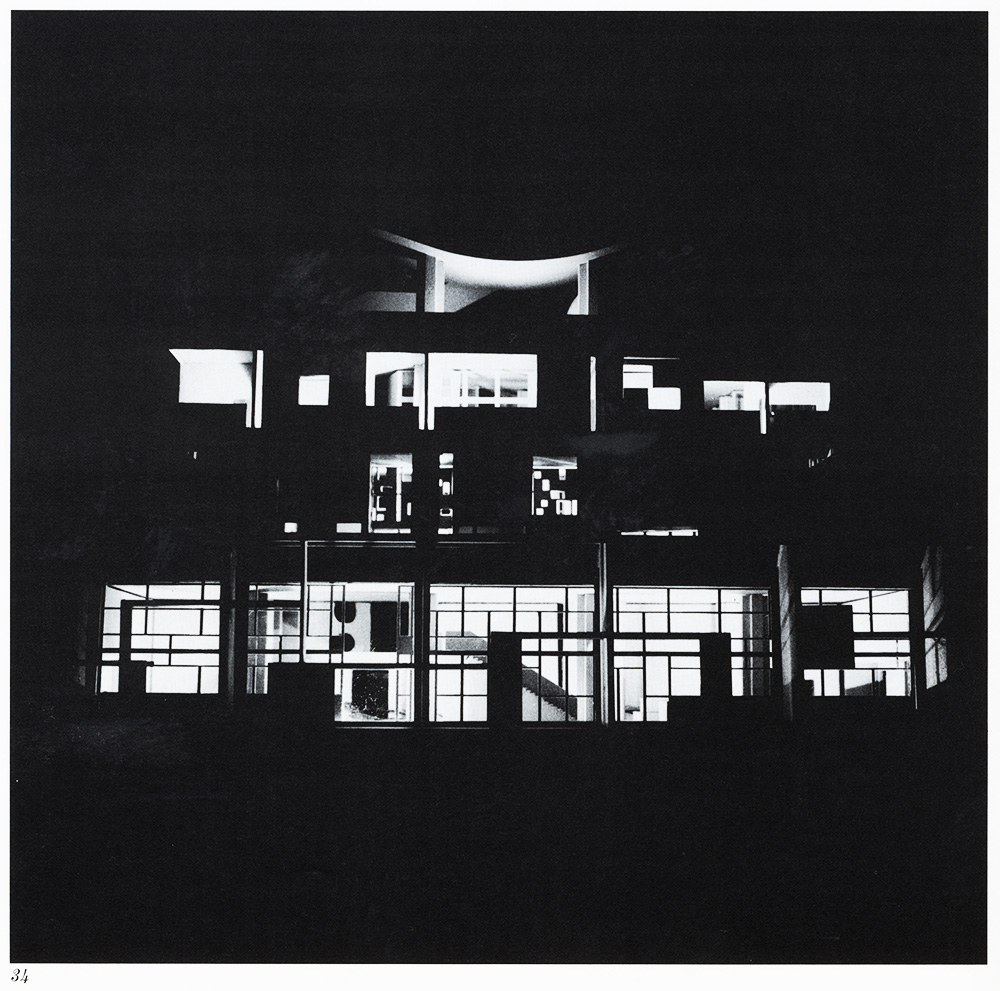

Solid and void are further utilized to flatten the pyramid through a figure-ground reversal of the rectangular punctures of the upper level with the similarly sized and shaped panels on the brise-soleil. The upper frame is proportionally reduced, giving the impression of the voids denying their immateriality and popping out in space to the frontal plane below. Tiny, square windows between these levels provide a distant background for this illusion to occur. At night the relationships are reversed; the voids become white floating rectangles in the black sky (figs. 34, 36).

In the development of the elevations, the dual articulation of both solid and plane again contrasts traditional and modern conceptions of volume. Separated into their horizontal and vertical components, the volumes of the palace become equally a conceptually modern construction of thin planes and a series of pyramiding, stacked solids. For example, in the cantilevered level of the governor's apartment, the extension of the incised, punctured plane above and its slotting below are opposed by the diagonal cut of the corner indicating solid (fig. 35). This double meaning is clear in the massive sidewalls, where the canted medieval windows are produced by the shift of two screen walls of proportionally related squares, conceptually sandwiching a thickness between themselves. Mondrian's dictum that the reality is the space between the planes is here amplified.

The extraordinary complexity of the palace's monumental pedestrian entry is articulated within a frame of strict bilateral symmetry. Countering the symmetric frontality if this facade is an asymmetric rhythm of solids and voids, rotating the eye to the sides. At the sides the condition of the symmetric core is reversed to a dominant asymmetry, created by the addition of barsati, brise-soleil, and elevator tower. Through this additive-subtractive ordering method, symmetry and asymmetry become variations of each other, two seemingly opposed conditions resolved into one.

This dual articulation characterizing the formal strategy of the Governor's Palace can be contrasted with Le Corbusier's World Museum of the Mundaneum presented in 1927. Here the stepped pyramid is too close to its historical prototypes; as Le Corbusier writes, "its spiraling tiers recall Ninevah or Mexico." In the Governor's Palace, the highly developed tension between past and present serves both to preclude the literalness of historicizing quotation and to provide a link with Indian thought. Thus, Hindu philosophy, dualistic in nature, invests certain formal oppositions like solid-void with religious significance as models of universal truth. Perhaps it was Le Corbusier's own dualistic mode of thought that enabled him to establish conceptual parallels with the ancient forms and meanings elaborately developed in Hindu philosophy.

The symbolism of the palace can be understood as Le Corbusier's conscious confrontation with India as he attempts to conjure ancient sacred themes alongside modern myths. It is an approach which explores the capability of certain forms to accept meaning. In many instances, related images are introduced late in the design, and the overlay of such interacting, seemingly contradictory images is eventually resolved in the personality of Le Corbusier. For Le Corbusier, the experience of India had a personal meaning. He publicly avowed the "necessity of satisfying Indian needs and ideas rather than imposing Western aesthetics and ethics," and later spoke of "possible contact, in Chandigarh, with the essential delights of Hindu philosophy, fraternity between the cosmos and living beings." Uniting the symbolism of the palace is Le Corbusier's metaphysical theory concerning harmony propounded in Vers une architecture, in which he links man, architecture, and the machine. Both significant architecture and certain machines are "felt to be harmonious because they arouse, deep within us and beyond our senses, a resonance, a sort of sounding board which begins to vibrate. An indefinable trace of the Absolute which lies in the depths of our being." Harmony, then, is "a moment of accord with the axis which lies in man, and with the laws of the universe-a return to universal law." Both the airplane and the Parthenon had "recovered the axis."

Thirty years later in the Governor's Palace, Le Corbusier confronts his modern metaphysic with traditional Indian conceptions of the sacred. Le Corbusier's axis uniting man, architecture, and the machine is joined to the mythical theme of the central axis of the world and man. In its complex pyramidal massing about a central axis and its crowning of the triple axes of the capitol, the Governor's Palace reinterprets the sacred themes of transcendence in both its communal and individual variants. The stepped pyramid as the axis of the universe and the world mountain linking heaven and earth are analogous in Indian mythology to the body of the Universal God. In yogic thought, each individual is a microcosm of the world whose own central axis enables him to ascend to the Divine within, liberating himself from material nature. Of the various sets of overlaid imagery revolving about these themes, the first evidence appears in Le Corbusier's drawing for a concrete bas-relief depicting the front facade of the Governor's Palace held between a bull and the crescent moon (fig. 46). As the only work of his architecture considered special enough by Le Corbusier to be taken out of context and isolated as a symbol, the bas-relief's significance unfolds in relation to its adjacent signs.

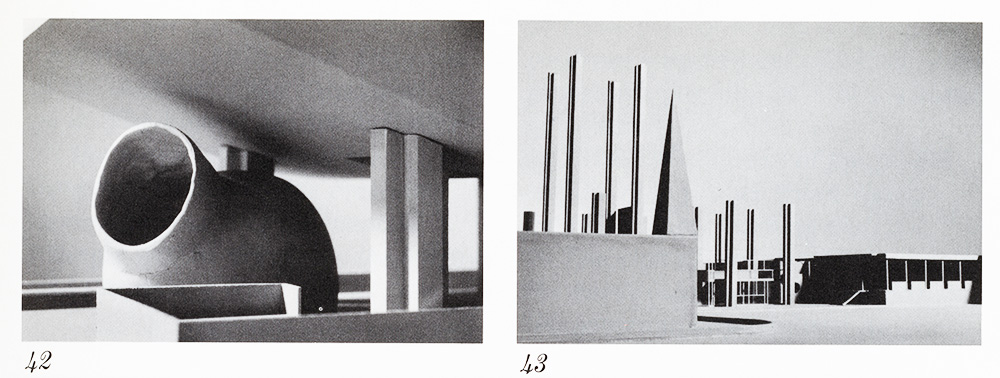

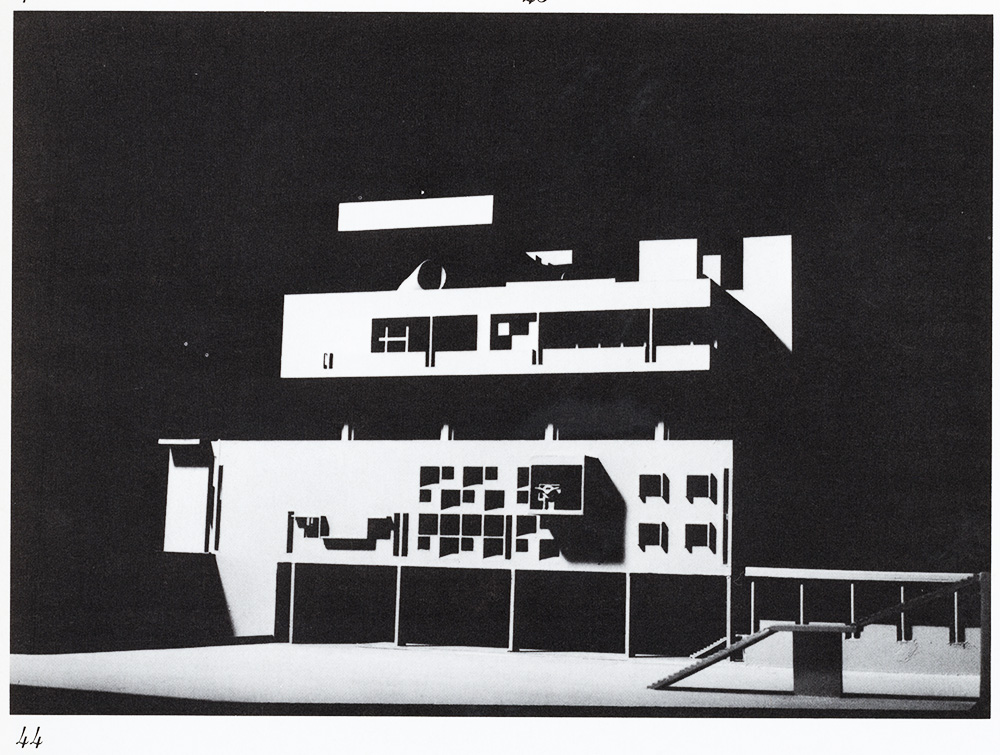

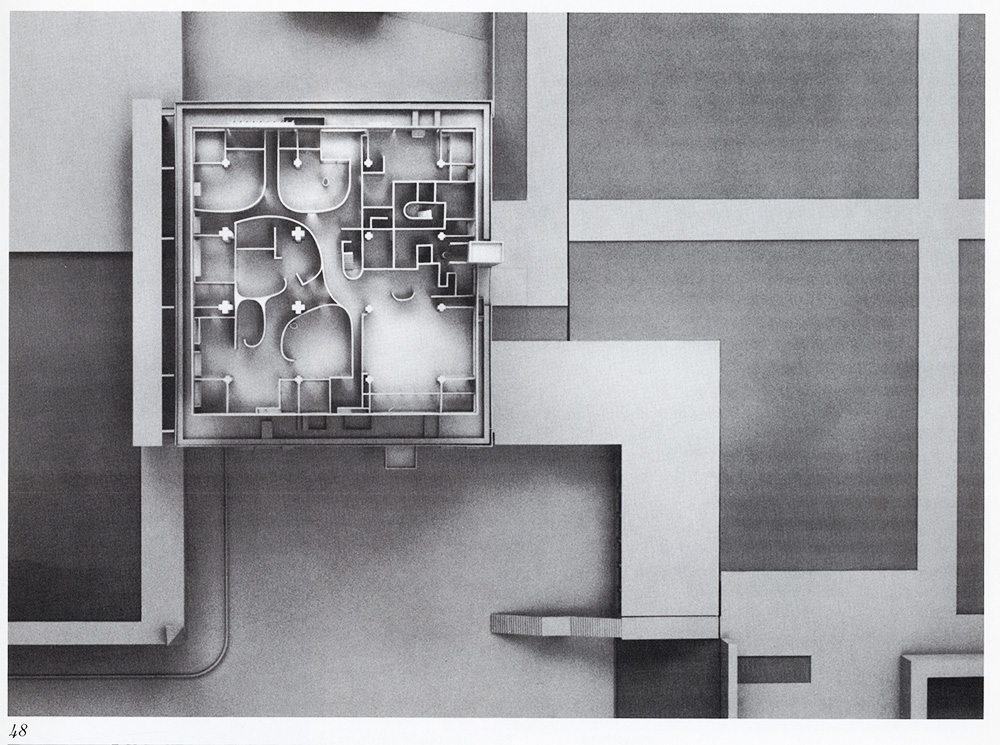

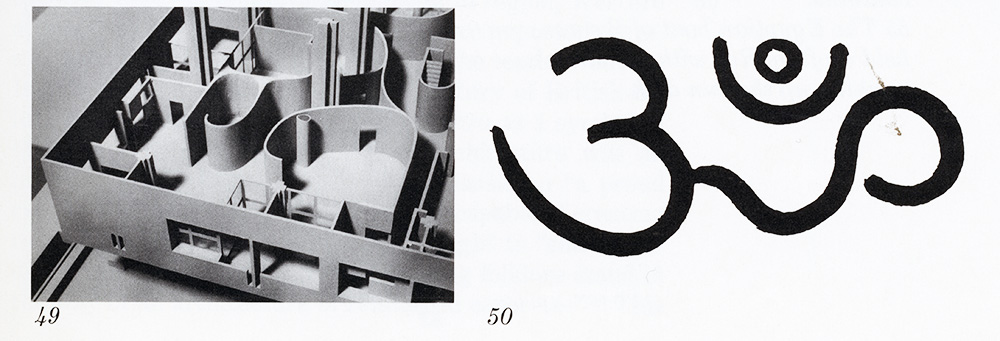

The relationship between the curve of the barsati and the horns of the bull is given by Le Corbusier in sketches of bulls adjoining sketches of the "plastic conception of the capitol" (figs. 38, 39), and quite literally in one of his "Taureau" paintings of the early fifties entitled Atlas Chandigarh. In the context of Hindu iconography, the bull, the crescent moon, and other images in the palace coalesce about the symbolism of the Hindu god Shiva. As one of the Hindu Trinity, Shiva manifests and unifies the duality of existence, simultaneously the sensuous cosmic dancer and the chief ascetic. It is through the symbolism of Shiva that the Hindu set of images are ordered in the Governor's Palace. For the bull, his horns crowning the palace, is Nandi, the animal vehicle and emblem of Shiva. 12 The curving barsati, the "horns" now of the crescent moon, again indicates Shiva, and in section, the prayer room takes the form of the most common Sivaite symbol, the lingam or phallus (figs. 37, 40, 41, 42-45). It is usually grouped with its feminine counterpart, the inverted triangle of the yoni. Thus in the palace, the prayer room is attached to the base of the central inverted triangle, together lingam and yoni, solid and void, signifying the duality in Hindu thought. Finally, there is the extraordinary correspondence of the curving walls of the governor's apartment to the sign "OM," sound and embodiment of Shiva as the Absolute (figs. 48-50). Virtually the same shapes as the Algiers apartment blocks, they are here rearranged to take on new meaning. 13 Although the sign does not appear in the first design, its introduction elaborates meanings latent in the idea of the Palace as a Hindu temple.

The references to Shiva as the specific deity of the Governor's Palace is explained by his role as the chief yogi, and thus in charge of the esoteric yoga doctrine of the Kundalini. This is conceived to be a serpent power residing in the base of the spine which through yoga exercises is forced up the central axis of the body in two intertwining spirals (recalling the red and blue spirals of the Modulor). It passes through a number of lotus centers or chakras in pursuit of the goal of liberating the Self by unification with the Divine. It is in the symbol of the highest chakra that the placement of the Hindu images is established. The images appear in the palace in the same relationship as in the chakra symbol (see figs. 17, 47). At the peak of the vertical axis where the barsati crowns the palace, the crescent moon surmounts the inverted yoni triangle, complemented within by the lingam and the sign of Om, together symbolizing the transcendent state where "one witnesses divine revelations day and night." The biological analogy of Chandigarh as body and head is extended to the metaphysical; the experience of the building, spiraling from dark to light, is ordered as a mystical journey within the self, beginning at the center of Chandigarh and culminating above the roof of the Governor's Palace.

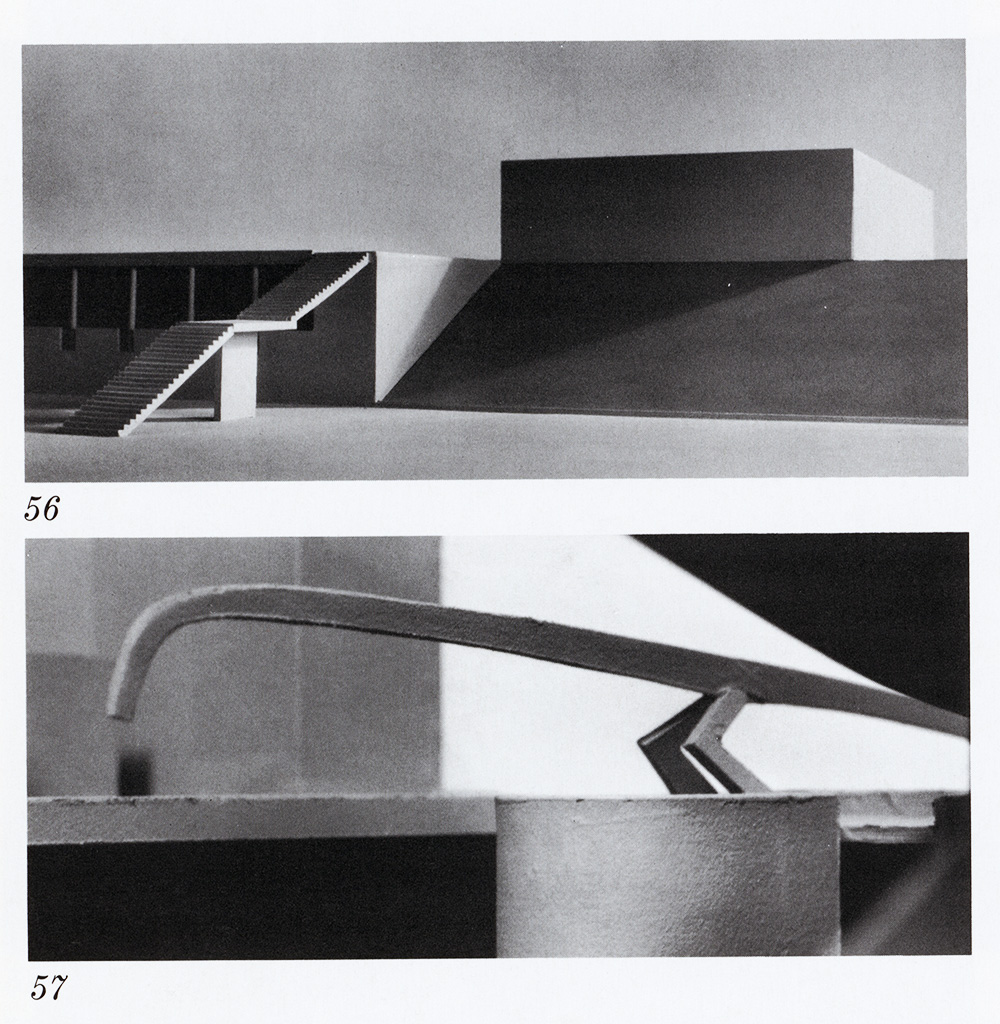

As Mircea Eliade writes, "the phases of the moon give us, if not the historical origin, at least the mythological and symbolic illustration of all dualisms." Thus the image of the moon in the palace is countered by that of the sun in a set of ancient symbols from the East and West. As the Tibetan yogin attempts to unify the symbolic opposites of sun and moon, Le Corbusier takes the form of the barsati, already articulated as horns and crescent moon, and infuses it with the image of the Egyptian sun boat (fig. 54). The diagonal of the ramp facing the palace visually severs the curving boat from its columnar base. Sailing up the ramp, it recreates the daily journey of the Egyptian sun god Ra across the sky. The vertical thrust of the supporting columns through the elevated water trough mirrors the Egyptian painting of morning, where a god rises from the primeval waters, his raised arms holding aloft the boat of the sun (fig. 55). On the side of the ramp is a symbol that is equally the Buddhist Wheel of the Sun and the Law. Yet another ancient reference made by the barsati and columns, it appears on the ceremonial gate at Sanchi. In the Buddhist search for Nirvana and the Egyptian pursuit of immortality, the theme of the transcendence from mundane reality to a higher plane of existence is joined to the Hindu symbolism.

(Images: 47_Image-606x1024.jpg)

47. Governor's Palace, Chandigarh. Le Corbusier, 1950-1953. Diagram of the chakras of the Kundalini yoga. The highest chakra includes all the major symbols of the Governor's Palace-the crescent moon surmounting an inverted triangle within which are the lingam and the sign of Om.

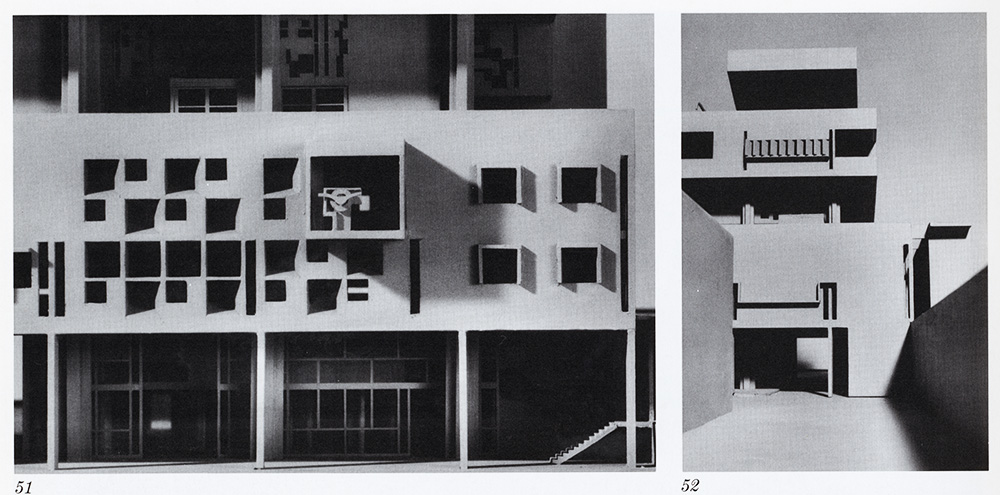

Corresponding to the ancient images of water (solar boat) and sky (crescent moon) are two twentieth century icons, the ship and airplane. Believing they touched the metaphysical axis of man, Le Corbusier equated them with sacred architecture of the past. The pedestrian views the ancient solar boat and the sculpture of the wheel on the ramp below as if gesturing to the cars speeding by. For from the road; the flank of the garden wall and the Palace atop its plinth become the hull and superstructure of a battleship or aircraft carrier (see fig. 30). The image of the Villa Savoye, the "machine for living," here becomes the captain's cantilevered bridge of the ship of state. Completing the machine imagery is the shift from water to sky. As the auto turns left to the lateral view of the columns lifting the barsati above the cantilevered volume, the image of the struts, wing, and cabin of the Farman Goliath in Vers une architecture appears. As in his book Aircraft, Le Corbusier pays homage to the machine which recovered the axis (figs. 52, 53).

Embodying the overlapping meanings of the palace in a single form is the sculpture facing the vehicular entry (fig. 51). At once it is the plane's propeller, the ship's steering wheel, the solar boat, and the horns of the bull-all united in the personal imagery and symbolic aspirations of Le Corbusier. Again, at the summit of the Governor's Palace, atop the central stair, the sculpture of a bird, archetypal antagonist in both East and West of the serpent, in his Kundalini and Modulor guise (fig. 57). In its location it recalls the Temple of Borobadur in Java, where the life of the Buddha is traced to his final Nirvana. The bird's stance is that of the raven, the corbeau - alias Le Corbusier, now the "Corbuddha." In this pun on his name, Le Corbusier is the heroic, Divine Architect, the one who will bring modern architecture to India and give form to native ideas.

It is in this context that Sigfried Gideon wrote of Chandigarh as the realization of the "attempt to meet cosmic, terrestrial and regional conditions," giving a more profound meaning to a modern architecture that professed to have international significance. Rather than ignoring the problem of foreign iconography or dealing with it in a superficial way as in Gropius's Middle Eastern projects of the 1950's, Le Corbusier proposes a universal solution, neither condescending to Eastern culture nor inimical to his own Western culture. Interestingly, the precedent already existed in the Punjab, of which Chandigarh was to be the capitol. As part of the Gandhara region, Western artists from the Roman Empire were once imported there, and created some of the first images of the seated Buddha. In this century, recovering from a century of British colonialism, Chandigarh was seen by Nehru as a symbol of the future. Observing that Indian architecture was an imposed foreign mix of Tuscan and Classic on "a proud culture with a thousand year history" incapable of creating its own architecture, Le Corbusier sought to "satisfy Indian needs and ideas," while "not letting folklore stand in the way of an architecture of reinforced concrete." This dualistic attitude is resolved in the Governor's Palace where Le Corbusier recognized the cross culture validity of certain mythical themes, creating a sacred work embodying the highest symbolic beliefs of Hindu culture while synthesizing them with ancient and modern Western myths. Thus Le Corbusier's physical isolation of the Governor's Palace from other buildings on the site becomes clear; as a sign to be imprinted in the concrete of Chandigarh, it is a modern symbol of the attempt to transcend culture and self, its references to traditional imagery highlighting its new, inclusive meaning. As Mircea Eliade writes, "each new valorization of an archetypal image crowns and consummates the earlier ones." Just as the apparent contradiction between the hull's horns and the crescent moon had in the past been resolved, so Le Corbusier attempted to fuse these image; with the machine, united in the mythical notion of transcendence (fig. 56).

Therefore, in its deepest sense, the Governor's Palace represents the idea of architecture as a challenge to man. In contrast to the Baroque palaces where man stood at the center, here the focus is shifted to the center within, which can only be reached by an inner struggle. By placing man's image on the Governor's Palace, Le Corbusier identified this work with the theme of his last essay: "when you finally get down to it, the dialogue, the basic confrontation, can be formulated like this, man face to face with himself, the wrestling of Jacob and the Angel within the human soul."

Ironically, the mighty theme proved its own undoing, the governor chose to live in town and the palace was not built. The tragedy is that in Chandigarh, India, the challenge was not met.