Gorlin on Sir James Stirling - Architectural Record

Within Louis Kahn's burnished steel jewel box, the Yale Center for British Art at Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut. is a remarkable exhibition of the recently forgotten British architect Sir James Stirling. Co-produced by the Yale Center and the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, this sly show is a sleight of hand. Guest curator Anthony Vidler, dean of The Cooper Union's architecture school in New York, avoids making any conclusions about Stirling's work. Nevertheless, he has organized the exhibition into thematic categories that shed light on the contradictory work of this controversial master. At the time of his early death at 68 in 1992, Stirling was wildly popular, although mainly among architects. Today, in part because of the extraordinarily rapid MTV-Iike cycle of fame, most young architects have never heard of him.

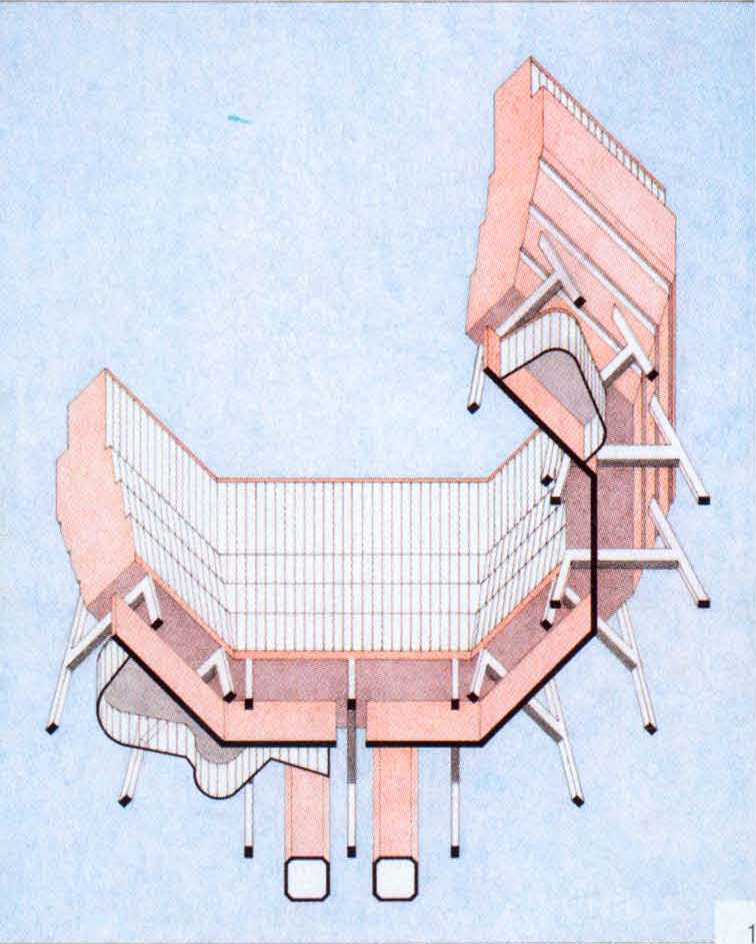

Axonometric, Florey Building, Queen's College, University of Oxford, 1966-71.

Stirling's career fits mainly into two parts- the first a robust revival of Modernist abstraction and materiality found in his Engineering Building at Leicester University (1963). At the time, it appeared to be a shockingly raucous cacophony of Russian Constructivist and Victorian-like shapes of brick and glass. Although a series of related buildings - such as the History Faculty Building, University of Cambridge (1968), and the Florey Building at Queen's College, University of Oxford (1971) - followed, Stirling soon abandoned this line of endeavor and merrily embraced the exploration of historical form. ln retrospect. some of these works look suspiciously close to the worst excesses of Postmodernism, rivaling those of Michael Graves, FAIA, or Robert Stern, FAIA. None of these projects approached the classic finality of Leicester, except perhaps the Neue Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart (1984). Meanwhile, a number of his buildings, including housing in England at Runcorn (1977) and Preston (1962), have been torn down, and even those at Leicester, Oxford, and Cambridge have been plagued by faulty workmanship. Today, when one is either thoroughly modern, a Ia Rem Koolhaas or Herzog and de Meuron, or traditional, like Allan Greenberg, few attempt an architectural synthesis, and therein lies the retrospective's appeal.

James Stirling, ca. 1960.

It is fitting to have the show, aptly titled "Notes from the Archive," open at Yale University, where Stirling was a yearly fixture, teaching from 1959 to 1983. (He was also a professor of mine.) Here can be found the extraordinary and fairly quaint testaments to the talent of this architect's architect in the period just prior to the age of digital design. Tiny hand sketches and doodles, drawings on yellow trace, paper models, and other arcana are on display in a drily presented installation.

However, there should be a sign at the entrance: "Abandon all hope of learning anything about why James Stirling was considered so great. unless you already know his work in detail."

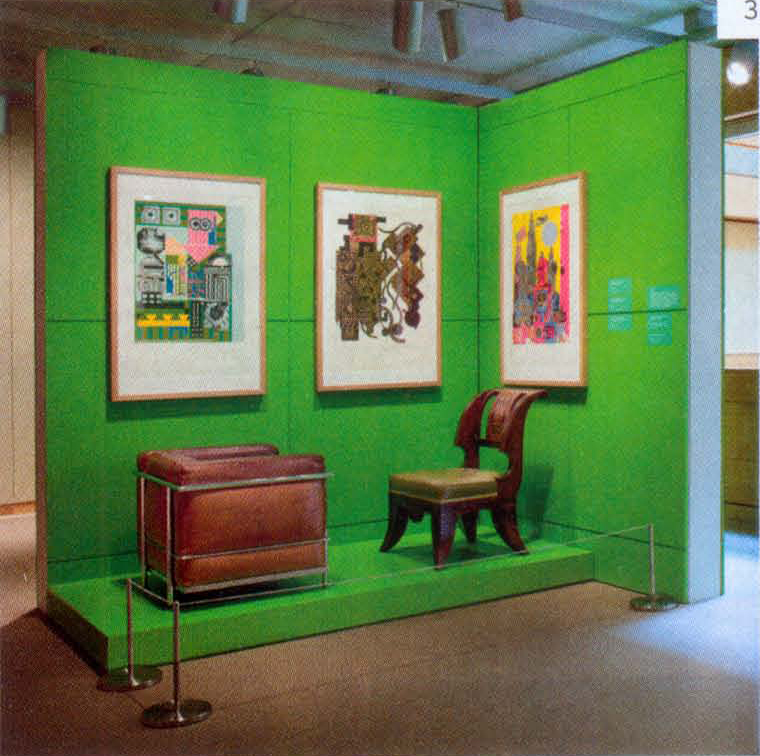

The show includes Stirling's favorite objects: the "Grand Contort" chair, 1929, by Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand (left); the English Side Chair (Hope Chair), ca. 1802-10, from a design by Thomas Hope; and prints by Eduardo Paolozzi, all 1965.

In contrast to most contemporary shows about architects, this one is similar to an exhibition of medieval miniatures: It is for connoisseurs and aficionados of the one-inch-plan diagram that magically, by spell and incantation, becomes a full-fledged work of architecture. Only architects, critics, and the most knowing admirers of the genre can make any sense whatsoever of these artifacts. Oddly, the most lucid part of the show is the presentation of Stirling's student thesis at Liverpool University's School of Architecture, which has numerous drawings, including one of a naked woman frolicking in a bedroom.

Perhaps the most memorable part of the exhibition is leaving it and being confronted by the massive concrete cylinder of the main stair in Louis Kahn's museum, in which the Stirling show is ensconced. Here, then, you imagine two masters, Kahn and Stirling, in a metaphorical dialogue about the fundamental nature of architecture. One knows, of course, that in a real-life conversation, the rowdy Stirling would shout out something improper or outrageous. He liked to shake things up-- just as he did through his often-radical architecture.